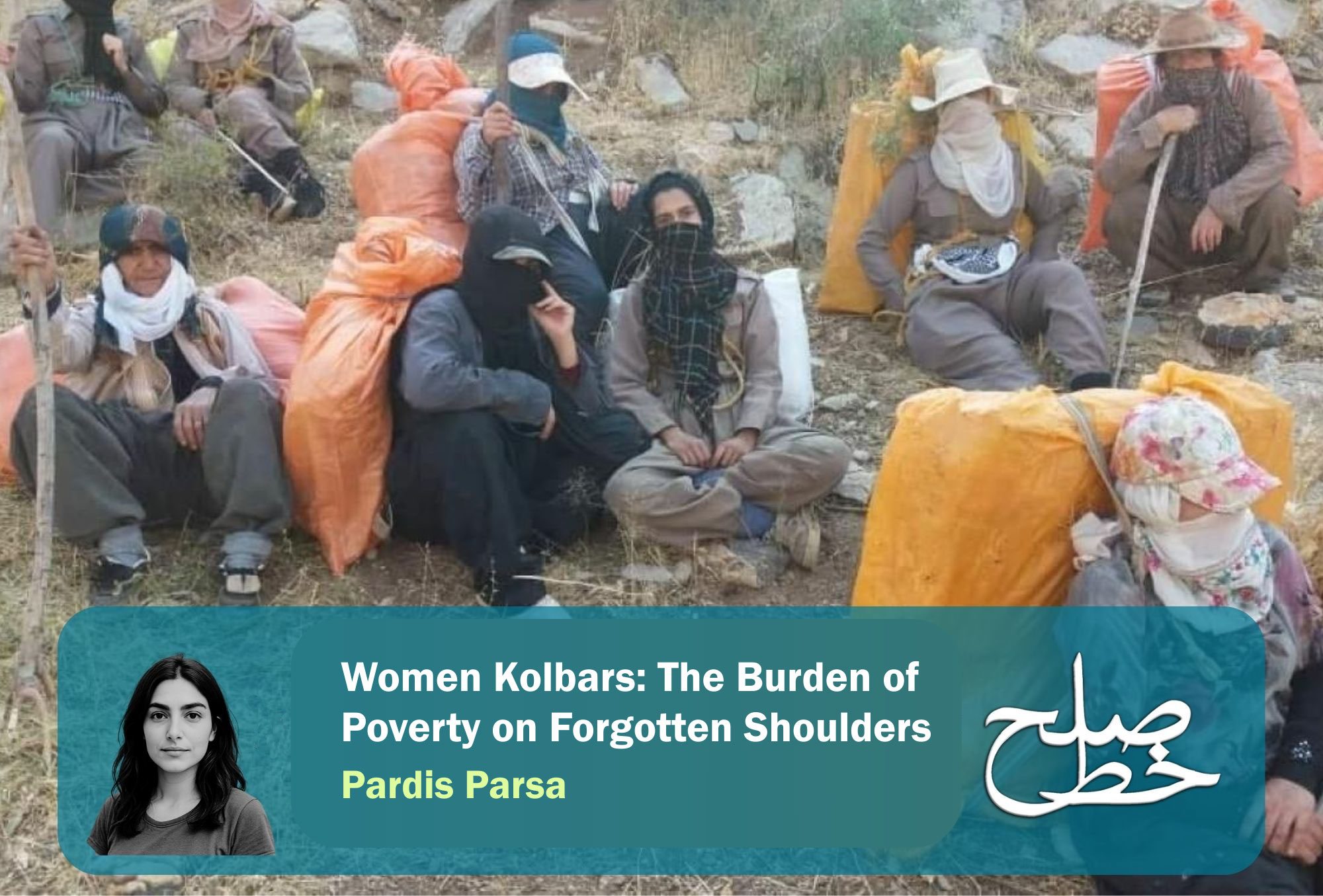

HRANA- This article, published in the peace Mark monthly, recounts the various hardships of kolbari through the voices of women kolbars. Kolbars are laborers who, out of poverty and in order to make a living, carry goods on foot across Iran’s borders, particularly along its western frontiers.

Read the full text of the article below:

Kolbari, a practice most common in the provinces of Kurdistan, Kermanshah, and West Azerbaijan, is a phenomenon tightly intertwined with structural poverty, underdevelopment, and centralized governance policies. The state, through continuous underdevelopment of non-Shia and non-Persian regions, has exacerbated this issue—particularly in the Kurdish border areas. Years of neglect, historical insecurity, and a securitized view of these regions have made sustainable investment virtually impossible. The absence of factories and manufacturing workshops, the weakness of tourism, and stagnation in agriculture have deprived locals of formal employment opportunities and driven up unemployment rates. In the absence of supportive and developmental policies, the informal economy and high-risk activities like kolbari have become the only means of survival and livelihood for thousands of border-dwelling families.

Unofficial estimates place the number of kolbars between 80,000 and 170,000. While there are no official disaggregated statistics on the exact number of women kolbars, some sources estimate it to be several thousand. Many of these women are heads of households or have husbands who are unable to provide due to illness or addiction. For these women, kolbari is the last bastion of financial independence and a means of covering their families’ most basic needs.

“Bahiyeh,” a 53-year-old woman who has been working as a kolbar for ten years, told Peace Mark Monthly Magazine:

“This is just how the world is. Some people have it easy. Others like us live hard lives and have to do kolbari to survive. My eldest son has a master’s degree and is unemployed. He doesn’t even have a penny in his pocket. His wife is educated too, but she’s also jobless. My other two sons are the same—one’s a computer engineer, the other’s got a master’s in accounting. None of them have proper jobs. What can I do? I’ve tried other things like making ‘giveh’ (traditional footwear), sewing, and knitting with yarn. But those don’t bring in money like kolbari. Without kolbari, we wouldn’t survive.”

“Golzar,” 48 years old, a widow who raised her six children alone, said:

“Nowadays, everyone’s doing kolbari to make a living. Life has gotten so expensive. Everything’s pricey. You have to go do kolbari two or three times just to buy a sack of rice. I’ve been doing this work for eleven years now.”

“Chiman,” 45, whose husband cannot work due to severe spinal disc herniation, said:

“Right now, I’m the head of the household. I’ve got three school-aged kids. We’re renting a place in Paveh, and I do kolbari in Dezavar. My daughter got divorced and came back home with a little child, and my husband has back issues. Now we’re seven people in the house. Kolbari is my main job. If I don’t do it, where would we get money to eat?”

Gender Dimensions and Discrimination

Compared to men, women kolbars are in significantly more vulnerable positions. They not only face the same physical dangers but also endure layers of cultural discrimination and pressure. In traditional and patriarchal views prevalent in some local communities, a woman’s presence in the harsh, male-dominated world of kolbari is considered inappropriate. Women who take on this work often face disdainful or pitying glances. This judgmental perspective exposes women kolbars to social isolation and intense psychological stress.

“Golchin,” a widow and kolbar for twelve years, shared:

“So many rumors have spread about us. They’d say we go to Iraq and do God-knows-what, or that we go with strange drivers. A thousand stories have been made up about us. I’ve heard them all. In the beginning, it really upset me. But now I don’t care anymore, because I know I haven’t done anything wrong. I just went, sold my goods at the Toyleh market (a village on the Iraq border), bought some items there, and brought them back to Iran to sell. I did it to raise my two kids and not have to beg anyone.”

“Golzar” also said:

“You know what the difference is between men and women doing kolbari? Men do their job and no one talks behind their backs, but with women, it’s different—especially if you’re a widow. There’s a lot of judgment about female kolbars. They say we go to Iraq and who knows what we do there. Of course, now that we’re older and have been doing this for a long time, people know us and what kind of people we are. But for young women just starting out, this issue still exists.”

The Double Burden of Gender Roles

According to gender roles defined by society, managing the household and caring for children are primarily the woman’s responsibility. For women kolbars, this means starting a “second shift” after hours of grueling physical labor in the mountains. Unlike men, who can rest after returning from kolbari, these women are expected to immediately take up cooking, cleaning, and caregiving duties without pause. This double burden intensifies their physical and mental exhaustion, leaving no room for rest or self-care.

“Roshana,” 22, who has been doing kolbari with her husband for a year and a half, said:

“House chores, cooking—it’s all on me. After we came back from kolbari, my husband would take a shower and lie down, but I had to go straight to the kitchen to make tea or cook. He never helped me. One time, I was really exhausted and his mom was with us. When we got back, I told myself I’d rest an hour before making food. But my mother-in-law criticized me so much and said I wasn’t fulfilling my duties, that I ended up dragging myself to the kitchen to cook while still worn out.”

“Maliheh,” 39, who’s been doing kolbari with her husband for two years, said:

“I do the housework, childcare, cooking, and even work in our garden. When I push myself too hard during kolbari, I can’t handle the rest. My eldest son helps me a lot, but most of the chores are on me. When I bring back heavy loads from Iraq and then come home to more work, I’m really exhausted. I can’t focus on anything—not my kids, not the house, not even the garden.”

No Physical Safety, No Peace of Mind

Treacherous mountain routes expose all kolbars to deadly risks—falling, avalanches, hypothermia, wild animals, and landmines leftover from past wars are constant threats. Violent encounters with border patrols and the risk of being shot must also be added to this list.

“Golzar” added:

“Sometimes the path we take has landmines. God has spared us so far. One time I tried to pass through Maleh Hendu but wasn’t allowed. So, I thought I’d go down from Kalle Ghani. I was about to step on a mine—only a hand’s width away. God helped me at that moment. I thought it was some metal trash. But when I looked closely, I realized it was a mine. If it had exploded, who knows what would’ve happened to me.”

“Bahiyeh” said:

“While returning with loads on our backs, suddenly patrols would show up. We had to hide behind rocks until they left. Sometimes we waited for three hours just to get back. By the time we got home, it’d be night. Sometimes we’d arrive at 2 or 3 a.m., in snowstorms even. They’ve seized or thrown away our goods too.”

“Shahin,” 31, who has been a kolbar for a year, said:

“The loads we carry are really heavy. Sometimes mine has weighed 30 or 35 kilograms. The path is so rough and steep—it’s easy to twist your ankle or fall.”

“Chiman” recalled:

“My mother used to carry kerosene in small bottles to sell in Toyleh. Sometimes it’d spill on her back and burn her skin. Her back would peel like old plastic. Carrying fuel comes with those kinds of miseries.”

The psychological toll is also crushing. Constant fear of death, worry about their children, feelings of humiliation and helplessness, and verbal and physical abuse severely threaten their mental health.

“Golchin” said:

“When I first started kolbari, my son was in first grade and my daughter was in fifth. I’d lock the door and leave them home alone. I worried the whole time—what if they get electrocuted or burn themselves? They were just little kids, but I had no choice.”

Worn-Out Bodies and Forgotten Femininity

Carrying heavy loads on rugged terrain over time causes irreparable damage to women’s spines, joints, and overall health.

“Golzar” said:

“Kolbari is hard for women. When women get older, they suffer from all kinds of pain and illnesses. I have arthritis and a herniated disc. Every night, I take painkillers just to lessen the pain in my shoulders and legs and sleep, so I can get up and go kolbari the next day.”

Kolbari doesn’t just wear down women’s bodies—it also distorts their self-image and sense of femininity. In the struggle for survival, attention to health and feminine care becomes a luxury, and the body is reduced to a tool for labor and endurance.

“Roshana” said:

“Women are better suited for administrative or official jobs. Otherwise, this kind of life wrecks everything. At my age, no other girl is doing kolbari. Among kolbars, I’m the youngest. Girls my age live in comfort, and I’m stuck in this life. The sun in the mountains ruins my skin, my body suffers, and my spirit gets crushed. When I’m out kolbari, I feel really ugly because I can’t always put on sunscreen, and the mountain sun really burns your skin.”

Accompanying Men: A Survival Strategy on the Border

Some women do kolbari alongside their husbands, brothers, or children. This is a smart survival tactic in the perilous conditions of border crossings. According to kolbars’ experiences, having a woman in the group may reduce the likelihood of violence, as border guards are generally more lenient toward women and rarely open fire on them.

“Roshana” added:

“I’ve been doing kolbari for about a year and a half, but very limited. I mostly go with my husband so he’s not alone and doesn’t get stopped by border patrol. We pretend to be checking on our garden and then sneak toward Iraq through it. My husband doesn’t let me carry heavy loads. He’s told me not to come many times, but I don’t want him going alone. I’d rather we face any danger together. If, God forbid, border patrol shoots, at least we’re together. Border guards don’t usually bother women. They rarely shoot at us. That’s why I go with him—to reduce the risk to his life. It gives me peace of mind.”

“Maliheh” said:

“My uncle was killed by a border patrol shooting. His four small children were orphaned. I’m afraid to let my husband go alone. I go with him. If a woman’s with the men, the danger is less.”

Absence of Institutional and Legal Support

Although kolbari has become a widespread feature of border economies, there is no legal framework or institutional support for kolbars. Their work is considered informal, and they are excluded from insurance, social support, or legal rights. In cases of accidents, injury, or death, no institution takes responsibility for supporting kolbars or their families. More tragically, in many cases where kolbars have been killed by border patrol fire, their families have been forced to pay for the very bullets that killed their loved ones.

“Shahin” told Peace Mark Monthly Magazine:

“Kolbari has no insurance, no future—nothing. It’s a limbo job. It’s not something you can do forever. The fear that one day you’ll fall ill or become disabled and can’t earn is always there. You have no peace of mind. If, God forbid, you get shot or step on a mine, no one will come and say, ‘Here’s a little money to cover your treatment or your life.’ The owner of the goods will just find another kolbar the next day. Even the families of kolbars who are killed or injured have to pay for the bullet that hit them. That means a family barely surviving, who’s just lost someone, now has to pay the government too.”

Kolbari, for women kolbars, is a battlefield on multiple fronts. These women are not only battling harsh nature and crushing poverty, but also cultural systems that refuse to accept their presence in this field—while simultaneously shouldering rigid gender-based responsibilities at home. What gets forgotten in all this is their physical health, human dignity, and femininity—concepts that, in the daily fight for survival, become luxuries. Survival tactics, like accompanying men to avoid being shot, are bitter proof that a woman kolbar’s gender is simultaneously her vulnerability and her shield. The story of women kolbars is not merely a tragic tale of poverty—it is an indictment of a system that has offloaded the consequences of its failures in development and social justice onto its most vulnerable citizens.

Written by Pardis Parsa

Originally published in Khat-e Solh (Peace Mark) monthly magazine on October 23, 2025.