HRANA News Agency – Human rights campaigners are increasingly worried that funding to combat the narcotics trade is providing indirect assistance to a judicial system that is engaged in what has been described as ‘a killing spree of staggering proportions’.

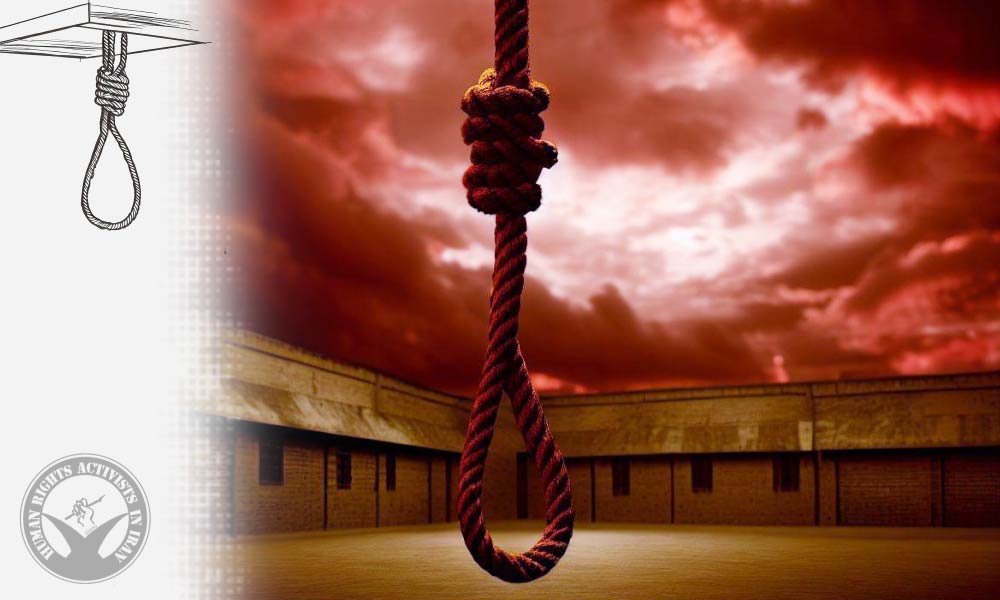

In Vakilabad prison, northern Iran, there is a long beam that can take up to 60 nooses. The condemned are made to stand on stools which are then kicked away. Vakilabad’s record is 89 executions in one day.

The true number of those executed in Iran is impossible to quantify, especially for those convicted of drug offences, but it is clear there is a large disjunction between official figures and the reality. In 2010 the Iranian authorities acknowledged that 172 people had been executed fordrugs offences. However, the Foreign Office is aware of credible reports suggesting the real figure could be at least 590.

In the 12 months to November last year, there were at least 600 executions, according to Amnesty International, 81% of which were for drugs offences.

And, among increasingly vocal human rights groups, the concern now is that the UK has unwittingly helped fuel the killing machine.

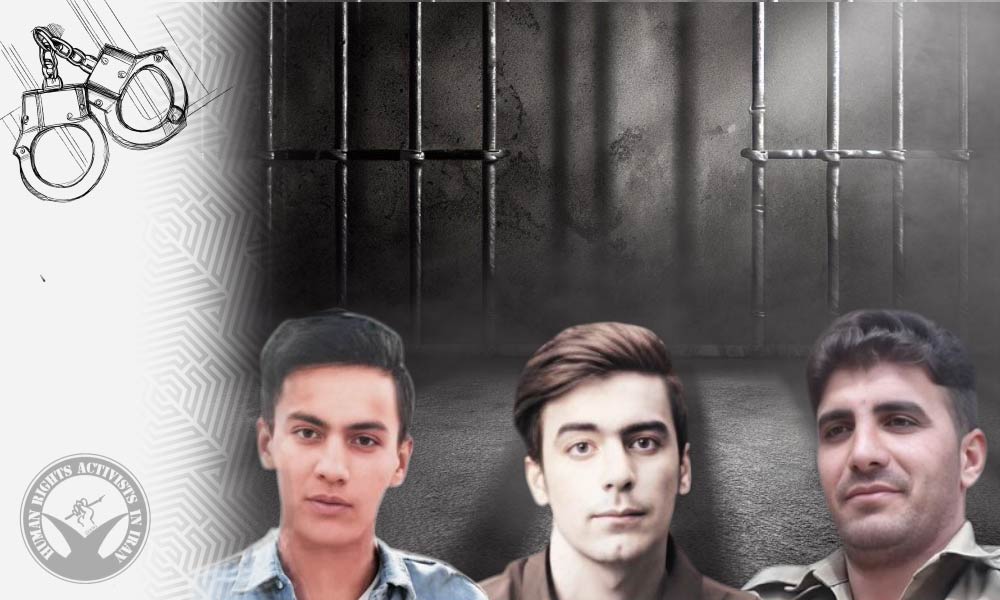

There is no shortage of those awaiting execution. It is estimated that as many as 4,000 Afghans alone are on death row in Iran for drugs offenses. There are reports that some are executed without a trial and that others are juveniles. Human rights groups claim that many of those executed come from the most disadvantaged sectors of society. Some are women. Many of those arrested have been duped into carrying drugs for others.

One man who was executed is believed to have been Haj Basir Ahmed, a 40-year-old Afghan, hanged at Taybad prison on 15 September 2011. He phoned his family at eight in the evening to say he had learned he was to be executed the following hour. His family have heard nothing since and his body has not been returned because Iran demands £10,000 for the repatriation of the executed. His is a typical case, according to human rights groups.

Such draconian treatment of pawns in the drugs trade would find little or no support in the UK, which abolished capital punishment in 1969. The foreign secretary, William Hague, has called the human rights situation in Iran “shameful”. But it has emerged that the UK has provided indirect assistance to an Iranian judicial system engaged in what Amnesty describes as a “killing spree of staggering proportions”.

Why the death toll is rising in Iran is open to conjecture. Some believe that the Iranian authorities are nervous about the Arab spring and are using drugs laws as an excuse to eliminate their opponents. But there is also a greater resolve in Iran to tackle the drugs trade which, the country’s authorities claim, has led to 1.2 million addicts. According to Iran’s annual Drug Control Report, in 2011 there was a “41% increase in arresting narcotics traffickers and distributors”. The report says that some 8,000 foreign nationals were arrested for drugs offences in 2010 and 2011.

Bordering Afghanistan, a country responsible for 93% of the world’s opium production, Iran faces a formidable challenge in combating trafficking. Those efforts have been given a considerable boost by the introduction of 200 sniffer dogs at airports and ports. Seizures attributed to the dogs jumped from 23,912kg in 2010 to 42,500kg in 2011.

According to documents obtained by the Observer, the UK was one of five donor countries that, via the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), gave almost $3.4m (£2m) to train the dogs. The four-and-a-half year project, which started in 2007, also provided specialised vehicles, satellite phones, drug testing kits and body scanners. It was not the UK’s only contribution to Iran’s counter-trafficking operations. In 2009 the Foreign Office confirmed that it had spent more than £3m between 2000 and 2009 providing counter-narcotics assistance in Iran.

Another UNODC document reveals that in August 2010 the UK and France pledged almost $730,000 to fund a two-year, intelligence-led, anti-trafficking programme targeting Iran’s borders with Pakistan and Afghanistan that “resulted in seizures of six tons of different types of drugs and arrests of drug traffickers”.

It is understood that much of the pledged money for the programme was distributed to another project outside Iran. However, UNODC documents reveal it provided the model for its “Iran Country Programme for 2011-2014”, suggesting it has left an impact.

Tackling trafficking through Iran – particularly heroin – is seen as crucial by western governments. UNODC estimates that 140 tonnes (37%) of the 380 tonnes of heroin produced in Afghanistan is trafficked annually through Iran and on to the European market. But human rights groups are concerned that the UK has supported a programme that has resulted in excessive punishments for often minor players in the drugs trade.

Even trafficking small amounts can prove fatal. In 2010 Iran introduced a new law prescribing corporal punishment for most drug crimes and the death penalty for anyone who “imports, produces, distributes, exports, deals in, puts on sale, keeps or stores, conceals and carries” more than 30 grams of a number of listed drugs, including psychotropic substances. “We’re talking about hundreds of people being killed by Iran every year because they carried some drugs across a border,” said Damon Barrett, deputy director of the charity Harm Reduction International. “These are mostly people living in poverty with no other options. Meanwhile, western donors, including the UK, as well as the United Nations, provide money and assistance to the Iranian authorities for drug enforcement.”

Iran is not the only country that uses the death penalty to have received UK aid. The UK was one of six countries that, via the UNODC, gave $6m to Pakistan last year and a further $11m in 2010 to support anti-drug trafficking programmes. The UNODC also has a counter-trafficking memorandum of understanding with six east Asian countries, of which five retain the death penalty for drug offenses. At least $26m has gone to these countries’ counter-narcotics programmes via the UNODC, almost a quarter of which came from the UK.

Now, however, politicians are questioning the wisdom of a policy that appears contrary to the UK’s own guidance to officials, who are warned that prior to providing assistance they must obtain assurances confirming that “anyone found guilty would not face the death penalty”.

As Hague writes in a foreword to the guidance, it is “in police stations, detention centers and court houses that the state exerts its greatest powers over individuals and so where fairness, human dignity, liberty and justice are most critical.” The European parliament has passed a motion expressing concern that money and assistance from member states “could lead towards increased death sentences and executions”. An early day motion signed by MPs has raised similar fears.

In May the UNODC published a paper that acknowledged it placed itself “in a very vulnerable position vis-à-vis its responsibility to respect human rights” if it funded countries that actively supported the death penalty for drug trafficking. The UN’s human rights council has warned that “co-operative assistance … could facilitate the apprehension of alleged drug offenders, who may be subject to the death penalty in violation of international human rights law”.

A government spokesman declined to give details about which countries’ counter-narcotics programmes it had funded. “We provide aid to a range of international partners to tackle the international drugs trade and minimise the threat it poses to the UK,” the spokesman said. “We take human rights very seriously and provide clear guidance to our officials. It is our policy not to disclose details about specific programmes or locations as to do so may reduce the effectiveness of this work.”

But human rights groups said that there was an urgent case for greater transparency. “We know that human rights abuses are rife in the war on drugs,” Barrett said. “At a time when every penny is being shaved off budgets, we deserve to know how much money the UK is providing for drug enforcement overseas, and what that money has achieved, beyond risking the UK’s complicity in abuse.”

By Jamie Doward, Guardian.co.uk