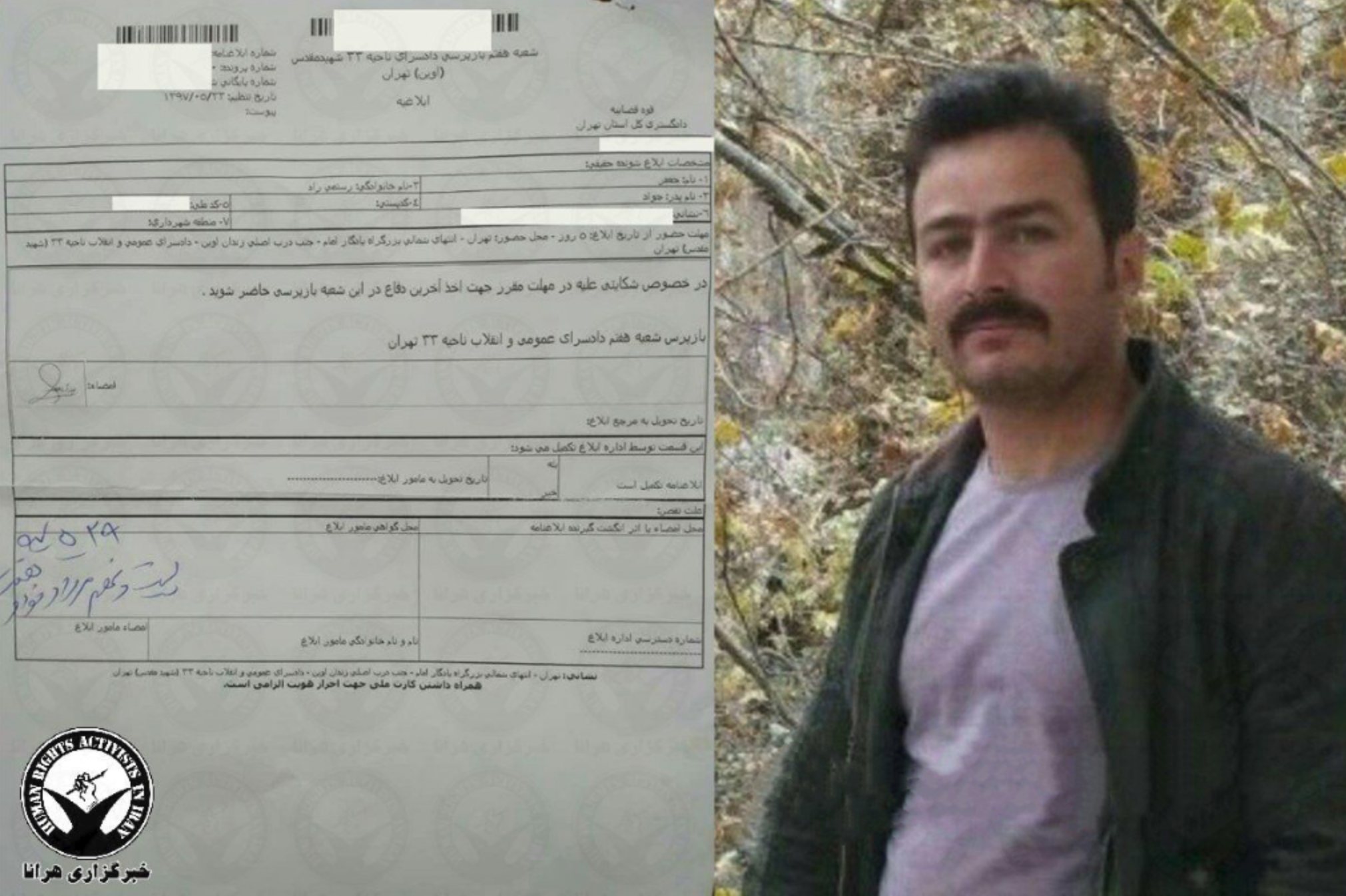

Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) – Released on Monday, August 20th after spending one day in the Great Tehran Penitentiary, writer, translator, and journalist Nader Faturehchi was moved to publish a post on Facebook about the miserable conditions of the prison’s quarantine ward.

Having been arrested the day before, Faturehchi was sent to the Great Tehran Penitentiary (also known as “Fashafoyeh”) when he was unable to post bail, HRANA reported. He was arrested pursuant to charges brought by Mohammad Emami, who himself has been charged with embezzling money from a pension fund for teachers.

Summoned to answer to Emami’s accusations on August 19th, Faturehchi wrote, “A serious battle with corruption has begun. I’m going to court, coerced to ‘explain myself’”.

Born in 1977, Faturehchi writes on politics, art, social issues, and philosophy.

Below is the translated text of his post:

I had a very short stay in Fashafoyeh Prison.

I write here not to describe “personal suffering”, but to deliver on a promise that I made to the inmates of the quarantine ward.

All that’s worth saying about myself is that I “went” to Fashafoyeh Prison; the judge had insisted I go to Evin [Prison], but I was transferred to Fashafoyeh instead. Unbelievably, prisoners are made to pay their own transfer costs (if they can afford it), and naturally the fee for a transfer to Evin (150,000 rials) [about $1.50 USD] is “considerably” different from the fee for a transfer to Fashafoyeh (1,000,000 rials) [about $9.50 USD].

At any rate, the greed of police agents afforded me a glimpse into the conditions of Fashafoyeh’s quarantine or “drug offenders” ward.

Among inmates, the colloquial name for the quarantine ward is “Hell”.

The accused, the convicts, the inmates awaiting transfer, or any other kind of “client” will spend four days in the quarantine ward before transfer to a ward known as “the tip”.

The prisoners said the difference in living conditions between the tip and quarantine wards are analogous to those between a bedroom and a toilet.

Having witnessed the quarantine ward on three different occasions in the 90s and 2000s, I can definitively corroborate their accounts of how “grave” the conditions in Fashafoyeh’s quarantine ward really are.

In a routine four-day quarantine period, the prisoner, no matter their crime or sentence, is deprived of potable water, ventilation, toilets, cigarettes, and digestible food (there is cold, half-baked pasta, and cold, uncooked yellow rice).

Fashafoyeh, designed for drug addicts with limited mobility, doesn’t have a public toilet. The toilet is a hole on the floor of a 2X2 foot area without light or running water, separated by a curtain from the ward’s beds and 10X10 foot cells, known as “physicals,” that house between 26 and 32 prisoners. The living conditions in the physicals are so inhumane that quarantined inmates call them the “place of exile”.

Quarantine cells have three-tier bunk beds and two blankets spread on the floor. Two glassless skylights are all they have to regulate temperature. There is no running water between 4 p.m. and 7 a.m., and the only light glows from a 100-watt fluorescent bulb. Should it burn out, the prisoners say, “only God could make someone replace it”.

The cells operate on an unspoken caste system. “Window beds” are reserved for convicts with longer sentences and greater street cred (lifers, drug-dealing kingpins, gang members, violent offenders and grand theft cases); ordinary beds (with no access to the skylight) go to lower-ranking prisoners (small-time drug dealers, pickpockets and petty thieves, etc.), while drug addicts, Afghans, and newcomers are directed to the floor.

Crowding at the prison evidences a mass daily influx of newcomers. Every 24 hours or so, more than 40 new prisoners are brought to the quarantine ward, while a maximum of ten [prisoners] leave the ward each day.

“Floor sleepers” — most often Afghans and intravenous drug addicts — endure conditions similar to those in “coffins”, the coffin-sized cells reserved for political prisoners in the 1980s that were barely large enough to lie down in.

In the cramped conditions, floor sleepers are sometimes pushed to spending the night beneath the beds of other inmates. Coined as “coffin sleepers,” it is typical for other inmates to sit on the floor next to their sleeping enclosure, restraining their movement and blocking their access to light and air.

The stench of sweat and infected wounds is unbelievable. Many inmates are detoxing from drug addictions and are in no state to be taken to the so-called “bathroom” to wash up, which thickens the stench.

More than 80 percent of quarantine inmates are intravenous drug addicts and homeless people unable to stand on their own two feet who belong in a hospital, not in a prison.

A single guard presides over the entire ward, a government agent, while the rest of prison labor (reception, maintenance, cooking, night watch, chaperoning for transfers and even medical work) is performed by the inmates themselves.

In addition to the guard, a mullah (cultural agent) and social worker count among the “staff” whose presence is of no use to the prisoners.

The prison machine is a hierarchical one. Representatives and monitors of each ward are usually white-collar convicts charged with embezzling and fraud. They bunk in cells with amenities like private beds and telephones and have the freedom to move around, smoke cigarettes, don personal slippers and even wear socks. One rung down from them are the “night monitors,” also financial convicts. The third rung down (reception, maintenance, kitchen staff) are theft convicts who have been in the “tip” for less than two weeks.

From what I’ve seen myself, the population of educated people in prison charged with white-collar crimes has spiked in recent decades. This invites an urgently relevant case study from a sociological point of view.

Aggression, insults, and mockery toward newcomers are natural, given that the prison is run by prisoners who, tasked with running the place, tend to be much more amenable to familiar wardmates. And while newcomers are met with brute force and verbal aggression, the guards develop compassion towards them after this initial hazing period has passed (intravenous drug addicts and detoxers are of course an exception to this rule).

I myself was spared insults or humiliation, both from the staff and the prisoners in charge, even though I arrived at the ward shackled hand and foot. For 99 percent of my fellow prisoners and even the staff, the charges against me were considered “incomprehensible, unknown, and strange.”

At no point did I experience disrespect, insults, or aggression, and though my status would have made of me a “newcomer and floor sleeper,” I was shown kindness and respect from the beginning by fellow prisoners, especially from the ward representative, monitors, administrative staff, police officers, and guard. My special treatment was made all the more obvious by the fact that I was the sole newcomer whose head was not shaved, as it is the protocol in quarantine. Drug addicts, theft convicts, “dirty ones” and Afghans are treated like livestock from the moment they step foot in the ward.

Fashafoyeh is a prison for nonpolitical cases and ordinary criminals who do not elicit media attention or human rights outcry, and that is the greatest criticism one could make of civil and human rights activists.

Drawing attention to conditions of the “ordinary prisoners” in Fashafoyeh is an urgent and immediate necessity. No one in Iran is more oppressed and vulnerable. They exist in the epitome of “inhumane conditions” and are victims of a twofold oppression. To bear this, even for one day, is beyond the power of the human spirit and will undoubtedly cause permanent trauma to their body and soul. Every day, the number of cases like these only multiply.

Above the entryway to the Fashafoyeh Prison is a banner reading “Great Tehran House of Regret.” And yet, beneath the physical and spiritual pressures awaiting inmates across the threshold, there will remain no heart with which to reflect. It is impossible to think, let alone regret.

Another deplorable element of Fashafoyeh is its perimeter. Families of prisoners sit in the desert outside, and no one (I.e. the few soldiers on outside duty) are ignorant to who is or isn’t contained there (either that or they don’t reveal to the families what they know.) This is critical when Fashafoyeh prisoners come from poor families who can only come by taxi, at a cost between 1 to 1.5 million rials [approximately $10 to $15 USD].

I met people in Fashafoyeh who had been arrested four days prior and had yet to receive their due right of a free two-minute phone call. For the prisoners from poor families, a call at cost could mean millions of rials.

As I left the prison, I met a group of Gonabadi Dervishes, including Kasra Noori, Mr Entesari, and others. Their kindness and camaraderie chased away the emotional turmoil I had faced in the hours before. To see them was like seeing a familiar face, a ray of light in a dark abyss. I will never forget the warmth of their smiles.

My conscience was deeply troubled after I was released from Fashafoyeh, and I don’t think I will be ever able to forget the horrible conditions my fellow inmates were living in. Seeing their living conditions and their eyes devoid of hope; the putrid odor of the corridors; people who had nowhere to go; cells like cages; their constricted breaths; all of these sensations left a deep wound on my soul. With every glass of water that I drink and every cigarette that I smoke, tears pour down my face.

My arrest is of absolutely no importance. Banish it from memory. The outpouring of media attention and kindness that surrounded my arrest embarrassed and even somewhat upset me. My case is the least of this country’s priorities, a speck in the current of deep human sufferings over this land. The living conditions in prisons, especially for ordinary prisoners, is too terrible for words.

To quote Paul Valery, “This is humanity, naked, solitary, and mad. Not the baths, the coffee, and the verbosity”.

Note: If I didn’t respond to the kindness shown to me by comrades and friends, it is because I was haunted by the grim plight of those who remain there, and for whom I could do nothing. I apologize to you all.

Photo: Half of the Bahman cigarette, gifted to me by one of my dear Dervishes. In my last moments inside, two cigarettes were given to me by Mr Moses, an inmate on a life sentence with a big heart. He put the cigarettes in my pocket and said to me, “Praise the Prophet, all of you, and pray for the freedom for all prisoners… go and never come back, kid”.