Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) – A group of political prisoners in Zahedan Central Prison have written an open letter to the UN General Assembly, asking them to lift the voice of Iran’s prisoners.

The full text of their letter, translated into English by HRANA, is below:

Dear Members of Iranian Delegates,

Sitting next to each other in the UN General Assembly, you are looking for a way to guarantee human rights among peoples, and to resolve issues, such as scarcity of resources and climate change, which have had a grave impact on human beings’ lives.

There is a group of your fellow human beings who are forgotten behind bars, their voices choked out and their rights quashed. These “domestic charity cases*” look to you for a solution. [*A translation of a saying often used in protests, with the approximate literal meaning, “A light that could burn at home is unholy if burned in the mosque.” It is an outcry against misappropriated resources, or excessive attention being placed beyond the borders when the country’s own needs are great].

Why is it that Iranian officials don’t spend as much time addressing prisoners’ rights as they do for the rights of free people? It would be nice if they could be as vocal on this topic as they have been in their discussions of global issues.

Is the reality what they’re telling us it is? How close to reality are the movies and documentaries produced to further their arguments?

To answer these questions it would suffice to briefly point out some of the sufferings of the prisoners being held across Iran, particularly in Zahedan central prison:

1. Legal Limbo: The number of individuals trapped in legal limbo has reached a crisis level. There are prisoners who have spent two, even ten years behind bars on a pending case. Their requests for clemency, conditional release, or sentence reduction go unanswered. The delay can be attributed both to a high backlog of cases and to hefty bail amounts. Bails typically exceed 5 billion tomans (approximately $300,000 USD) but can even peak as high as 12 billion tomans (approximately $7,000,000 USD) or 300 billion tomans (approximately $18,000,000 USD). Judiciaries stack multiple charges onto defendants so that even when a prisoner’s case is resolved, the next charge against them is only beginning. Even in cases where a defendant is acquitted, the judiciary will hit them with new charges, hitting reset on the cycle of legal limbo.

2. Prison Population: Heavy caseloads (or deliberate delay in trying cases), paired with defendants’ economic [inability to post bail], have led to a burgeoning prison population. The prisoners are so cramped that they have to contort themselves into alternate sleeping arrangements, some laying in front of the washrooms, other on staircases. In prisons like those in Esfahan and Mashhad [the 3rd and 2nd largest cities in Iran, respectively], prisoners even sleep on the roof of the bathrooms and showers. Scant space has devolved into additional problems: a tiny prayer room, a shortage of washroom facilities, cramped outdoor recreation space, lack of amenities, and low-quality, small-portioned meals after which many a prisoner goes to bed hungry.

3. Political Prisoner Legal Limbo: Political prisoners spend several years in limbo prior to their trials, and after conviction spend even more time in suspense on various judicial pretexts. Despite having spent 5 or 10 years of their sentences and being eligible for furlough and conditional release, they are denied such privileges. Political prisoners are neglected deliberately. They even face additional restrictions on their rights to family visitation.

4. Prisoners on the Death Row: The prisoners on death row spend years and even decades waiting for their cases to be resolved. Somehow, they fall through the cracks. While a memorandum has been issued commuting the death sentences of a number of prisoners convicted on drug-related charges, many of the eligible prisoners’ names have been left off the list due to prison overcrowding. Many of these prisoners are routinely given the run-around by authorities who refuse to provide any answers about their fate.

5. Torture: In all institutions, and at the Intelligence Ministry and Intelligence Unit of the IRGC in particular, torture remains a common practice. Prisoners–especially political prisoners–are subject to the most severe and cruel forms of torment. Even if a defendant is innocent, they will confess under duress and torture. Various torture techniques are used in Iran, but no authorities will speak of them. Despite speaking out against the torture and its widespread use, we have yet to see change.

6. Obstruction of Defendants’ Rights: Interference from individuals who are not officials of the Judiciary is a challenge hindering many defendants. Families of prisoners receive threats from people calling themselves “interrogator,” “expert,” and “prosecution representative,” who heckle and dissuade them from inquiring into their loved ones’ cases. Even lawyers are a target. Families are insulted and barred from entering the courtroom.

When a lawyer is not allowed in the courtroom, how is he to protect the defendant’s interests? The defendants have no opportunity to defend themselves, their lawyers are strong-armed from doing their jobs, and the lawyers already blocked from case inquiries receive threats of their own.

So how is a prisoner convicted?

Nobody sees or recognizes the supervisor judges. The supervisor judge visits the prison twice, during which he spends a total of only four hours. Families of prisoners who have been lining up along the prison wall to meet the judge since 3 a.m. bring to mind lines of families waiting on their allotment of bread and gas. Despite the long wait, 90% will not obtain an audience with the supervisor judge.

The director general of Sistan & Baluchestan prisons visits penitentiaries perhaps once a year, during which most prisoners do not even recognize him. These problems are not specific to Zahedan prison: they are mirrored in Birjan, Esfahan, Yazd, Mashhad, Kerman, Ahwaz, etc.

7. Courts: The problems cited above have their root in the courts. Each passing mention of our courts is tinged with despair and disappointment. They beget a panoply of problems, from excessively long temporary detentions and the growing list of legal limbo hostages to the harsh sentences doled out to defendants.

Other points of note are the slow pace of the legal process in which an appeal can last more than five years; the gaps in subsequent appeals which can be as long as three years; and authorities’ disregard of the torturous conditions under which confessions and comments are extracted from defendants.

For those who conduct trials, defense lawyers are an afterthought, especially for political and security-related cases. Guilty and innocent are sent to the gallows. Then they will publish false and misleading statistics, portraying themselves as watchdogs of human rights.

8. Furlough and Open-Sentence Hurdles: The prisoners who are eligible for furlough have to endure a long, laborious process, investing time and money to obtain the right to an open sentence [in which they can leave prison at designated intervals while continuing their sentence]. Their situation is deplorable. We outlined some of their problems in an earlier letter, but the fact is that these prisoners are a source of income for authorities.

These prisoners, especially those from impoverished and neglected areas such as Kurdistan or Sistan and Baluchestan, perform all sorts of drudgeries for authorities. There are more than a thousand of them indentured to these circumstances for anywhere between five and 20 years. They are not eligible for privileges like clemency or conditional release. Their remuneration is trivial, although they work full-time and have to return to prison by 6 PM. Imagine a prisoner who works in the village but is incarcerated in the city: the commute costs 20,000 tomans (approximately $1.10 USD) each way, but is paid at 200 to 300,000 tomans (approximately 15 dollars USD). Their salary will barely cover 10 days of roundtrip commuting, let alone other expenses. You may refer to our previous letters on the matter.

The points discussed in this letter are real violations of prisoner rights. Prisoners have no way of voicing their grievances to top-ranking authorities and have no hope that their concerns will be paid any mind.

We ask the United Nations and international associations to help lift our voice–which echoes the voice of all prisoners across Iran–to Mr. Rouhani [Iranian president], Zarif [Foreign Affairs minister], and all Iranian authorities who are so occupied with the current conflicts of the world, the middle east tensions, the oil, the nuclear proliferation, the sanctions and the pressure tactics.

Please ask this of Messrs. Rouhani and Zarif: “You speak of human rights and proclaim to be defenders of human rights. You claim that Iran doesn’t have any human rights problems. Do you not consider these afflicted prisoners as human beings? What rights do you envision for them? Why don’t you send an independent investigator to the prisons, to speak directly to prisoners and corroborate our written claims?”

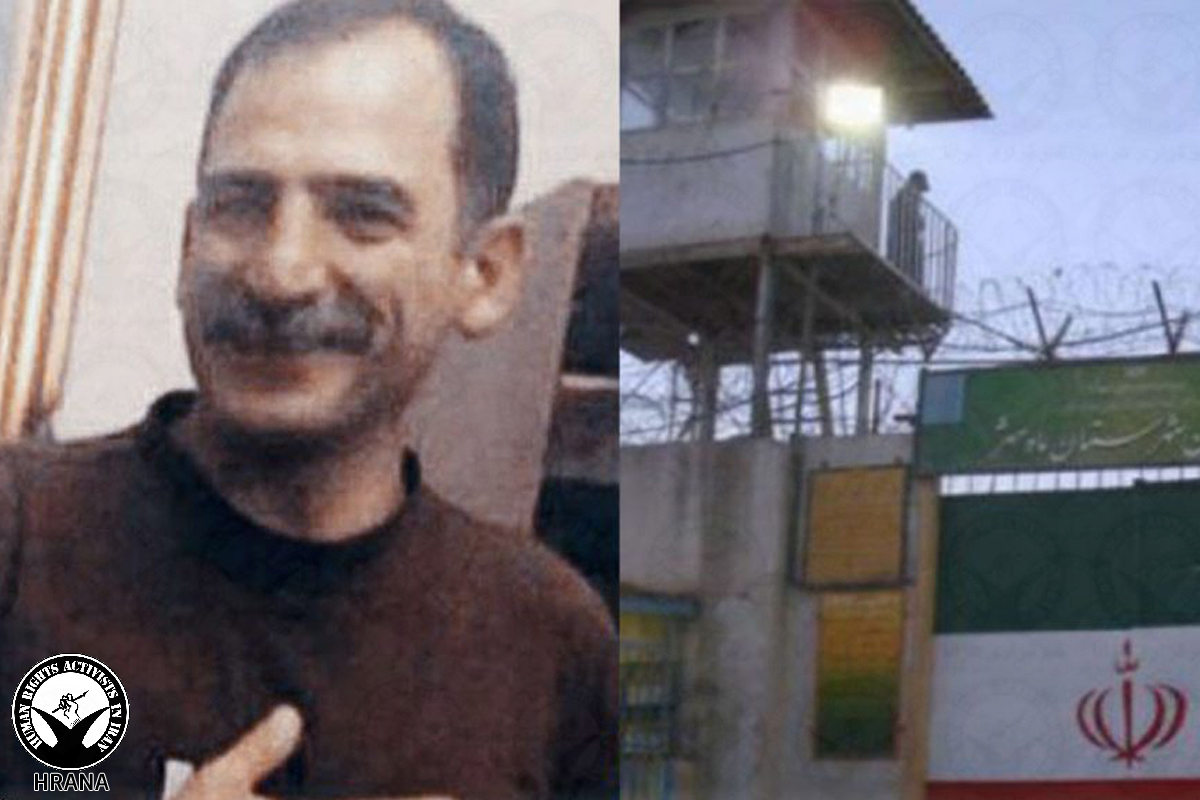

Political Prisoners of Zahedan, on behalf of all Iranian prisoners

Nour al-Din Kashani, Abdul Rashid Kuhi, Mohammad Saleh Shabadzadeh, Abdol Wahid Hut, Abed Bampouri, Ishaq Kolkli, Abdolkhaleq J Affadar Shahussei, Bashir Ahmad Hossein Zahi, Zubir Hoot, Ata Allah Hoot, Abdol Amir Kayazi, Abdolsam Hoot, Abu Bakr Rostami, Sajjad Baluch, Hamzeh Chakri.

September 26th, 2018