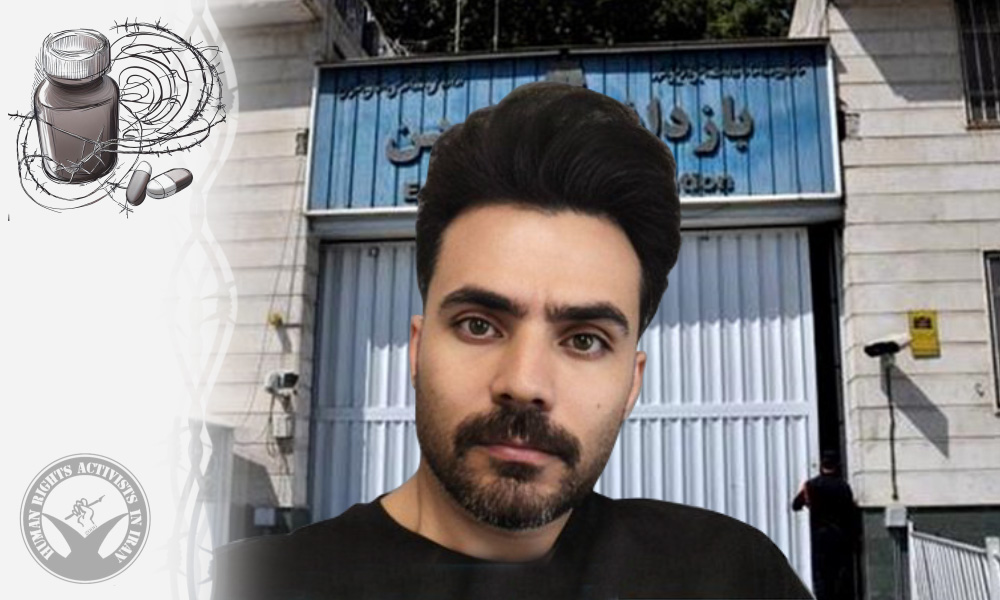

HRANA News Agency – Drug use is a pervasive issue within Iran’s prison system, driven by systemic corruption and inadequate oversight. These factors not only jeopardize the health and safety of inmates but also undermine their chances for rehabilitation. This report, based on interviews with prisoners’ families, former inmates of Ghezel Hesar Prison, and some of its staff members, delves into the mechanisms by which drugs enter the prison, the impact on inmates, and potential solutions to address this critical problem.

According to HRANA, the news agency of Human Rights Activists in Iran, drugs pose a major challenge in Iranian prisons, particularly in Ghezel Hesar Prison. The presence of drugs not only endangers the physical and mental health of inmates but also severely disrupts the security and overall functioning of the prison system.

Reports from the families of prisoners, individuals released from Ghezel Hesar Prison, prison staff, and HRANA’s independent analysis highlight the ease of access to various drugs, fueled by corruption among prison staff and a lack of effective oversight. Using this information, HRANA investigates the access to and distribution of drugs in Ghezel Hesar Prison in Karaj.

Access to Drugs in Prison

According to a former inmate of Ghezel Hesar Prison who reported to HRANA, access to drugs in this prison is surprisingly easy. Drugs are available at all hours of the day and in large quantities. Testimonies from families and relatives of those incarcerated in this prison indicate that the vast majority of inmates in Ghezel Hesar Prison are drug users, reflecting the widespread and severe nature of this problem. Drugs are easily found in all areas of the prison, from general wards to solitary confinement, and some inmates even openly use drugs in front of others.

Drug use in Ghezel Hesar Prison is not limited to habitual addicts; even inmates who were not addicted outside the prison turn to drugs due to psychological pressures and lack of supportive programs. These conditions have turned Ghezel Hesar into a place where addiction is rampant, rendering rehabilitation programs ineffective.

HRANA’s investigations from the families of prisoners indicate that the prison environment has become contaminated due to the abundance of drugs; the smell of drugs is constantly present, and even non-using inmates are affected by this environment. This situation not only harms the health of prisoners but also negatively impacts their morale and behavior, gradually pushing them towards drug use.

The Role of Corruption and Weak Oversight in the Entry of Drugs into Prisons

Drugs enter Ghezel Hesar Prison through various methods, with corruption among prison staff being the primary factor. A former staff member of Ghezel Hesar explained to HRANA that drug smuggling into the prison is carried out by certain groups that have close connections with some prison staff. These individuals include ward managers, jail trustees, and other influential groups who exploit weaknesses in oversight and corruption within the system.

This individual, whose identity HRANA has kept confidential, explained that corrupt prison staff, including guard officers, often turn a blind eye to drug-related activities in exchange for bribes. In some instances, these officers are directly involved in the smuggling and distribution of drugs. Rather than confronting those engaged in drug sales, they frequently accept payments from the sellers to allow the illicit activities to continue unchecked.

This issue clearly demonstrates the systemic failure of laws within the prison and proves that a serious and decisive response to this phenomenon is necessary.

Reports indicate that drugs also enter the prison through visitors and even the internal prison postal system. Inmates, often with the complicity of prison staff, use covert methods to smuggle drugs into the facility. The widespread and varied means of drug entry underscore the lack of effective oversight and control over the movement of inmates and their belongings.

Corruption in the Internal System and the Role of Prison Staff in Drug Distribution

HRANA’s findings reveal that prison staff play a significant role in the distribution of drugs within Ghezel Hesar Prison. Instead of preventing drug entry, staff members frequently participate—directly or indirectly—in the distribution process. Interviews with 30 former inmates indicate that some prison staff, particularly guard officers and security personnel, benefit financially from the drug trade, fully aware of the trafficking activities. According to these former inmates, guard officers often collaborate with drug dealers and protect them in exchange for bribes.

Jail trustees in each ward and other staff members also play crucial roles in the drug distribution network. Under the guise of their official duties, they deliver drugs to inmates and, in some cases, are involved in setting prices and managing the internal drug market. This entrenched corruption makes it nearly impossible to address the drug problem without a fundamental overhaul of the oversight system.

Inmates are also compelled to cooperate with these corrupt networks; otherwise, they may face violent actions and informal punishments from prison staff. These complex and intertwined relationships between inmates and staff pose a serious obstacle to any reform within the prison system.

Drug Pricing and Payment Methods in Prison

The prices of drugs inside Ghezel Hesar Prison are significantly higher than on the outside. A former inmate reported that drug prices inside the prison are, on average, ten times higher than outside, driven by the scarcity created by restrictions and the high profitability for sellers. Drug importers, often in collaboration with prison staff, manipulate prices, deliberately limiting supply when demand is high to drive prices even further.

HRANA’s research indicates that payments for drugs within the prison are not made in cash; instead, inmates use external bank accounts, often belonging to their family members, to transfer funds. This system allows sellers to profit from their illegal trade without the risks associated with handling cash inside the prison. Additionally, cigarettes are sometimes used as currency, illustrating the development of an internal economy within the prison walls.

This complex economic structure, fueled by a lack of financial control and oversight, enables the drug trade to thrive within the prison. Sellers and importers, protected by unofficial support and the absence of effective regulation, continue to reap substantial profits.

The Impact of Drug Use on the Health and Behavior of Inmates

Drug use within Ghezel Hesar Prison has severe consequences for the physical and mental health of inmates. Families of prisoners report that drug use has significantly deteriorated the mental and physical well-being of their loved ones, turning them into passive and unmotivated individuals. The presence of drugs in the prison environment has led to widespread physical ailments and psychological disorders, creating a toxic and dangerous atmosphere.

A recently released inmate told HRANA that the pervasive smell of drugs within the prison even affects non-users, who are often driven to start using due to the contaminated environment. The availability and use of drugs harm not only the users but also the entire inmate population, gradually leading to widespread addiction.

Drug Gangs and Control of the Drug Market in Prison

HRANA’s investigations, supported by inmate testimonies, indicate that the drug market within Ghezel Hesar Prison is dominated by internal drug gangs who exploit the system’s corruption. These gangs manipulate the supply of drugs, intentionally creating shortages to drive up prices and maximize profits. A former prison staff member, whose identity HRANA has kept confidential, revealed that these gangs distribute approximately five kilograms of drugs daily among inmates, with no oversight of their activities.

The individual further explained that these gangs, with the assistance of some prison staff and influential figures, control the drug market and effortlessly evade any legal repercussions.

Ineffectiveness of Current Treatment Programs

Although prisons offer programs intended to help inmates overcome addiction, these efforts are largely ineffective due to inadequate oversight and poor quality. According to informed sources, counseling and treatment sessions held in prisons are mostly symbolic and have not successfully reduced drug use. When the prison environment itself is the primary source of drug distribution and consumption, there is little motivation for inmates to quit.

Ghezel Hesar Prison, in particular, holds Narcotics Anonymous (NA) classes aimed at supporting addicts, but research shows that many participants in these sessions continue to use drugs. This underscores the fact that without structural reforms and the creation of a drug-free environment, treatment programs cannot succeed.

Conclusion

The Necessity of Adhering to International Commitments and Implementing Domestic Laws

The drug problem in Iranian prisons, particularly in Ghezel Hesar, is the result of systemic corruption, inadequate oversight, and the influence of mafia gangs within the prison system. This situation not only endangers the physical and mental health of inmates but also destabilizes the security and order of prisons. Addressing this crisis requires coordinated and decisive action by judicial, security, and prison management authorities.

As a member of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Iran is committed to implementing drug control programs, preventing addiction, and providing treatment services to inmates. These commitments oblige Iran to take preventive measures and reduce demand, particularly in sensitive environments like prisons, to curb the spread of drugs. Furthermore, based on international prisoner rights conventions, the Iranian government is responsible for providing humane and healthy conditions for inmates, including preventing addiction and offering appropriate treatment services.

Failure to uphold these commitments and address the current situation constitutes a clear violation of the international rights of prisoners, to which the Iranian government is bound.

According to Iran’s domestic laws, particularly the regulations set the Iran’s Prisons Organization, prison officials are obligated to maintain a safe and drug-free environment. These laws also mandate that inmates must have access to therapeutic and counseling services and undergo thorough medical and psychological supervision.

However, numerous reports indicate that these laws and regulations are often ignored in many prisons, with some staff directly involved in drug smuggling and distribution. This situation reveals that the existing legal framework remains largely theoretical, with little practical enforcement.

Proposed Solutions for Reform

- Stricter Oversight and Firm Implementation of Domestic Laws: There is a need for continuous and effective oversight of prison staff’s performance. Addressing corrupt staff members and establishing incentive systems for reporting violations could significantly reduce corruption and help control the drug problem.

- Strengthening Treatment and Rehabilitation Programs: The Prisons Organization should prioritize the quality and effectiveness of treatment programs rather than implementing them symbolically. This includes continuous staff training, employing scientific methods for addiction treatment, and providing specialized counseling to inmates.

- Increasing Transparency and Direct Communication Between Inmates and Judicial Authorities: Establishing direct communication channels between inmates and judicial and supervisory authorities, without the mediation of prison staff, could enhance transparency and reduce corruption.

- Utilizing Advanced Technologies in Monitoring: Installing and upgrading surveillance systems, such as CCTV cameras, and using advanced equipment for body searches could help reduce the entry of drugs into prisons.

- Pursuing International Commitments: The Iranian government should seriously pursue its commitments to the UN and other international bodies and provide accurate reports on its situation and progress. This not only helps improve prison conditions but also enhances Iran’s international credibility.

Ultimately, implementing fundamental changes and adhering to both domestic and international commitments can help reduce the drug problem in Iranian prisons, creating a safer and more humane environment for inmates. Without a strong commitment and effective collaboration among all responsible agencies, this crisis will persist, negatively impacting the health and security of society at large.